Retrospective Analysis of Recurrent HCV Viremia in High-risk HIV Co-infected People Who Inject Drugs (PWID)

Tyler Raycraft , Syune Hakobyan , Sahand Vafadary , Arshia Alimohammadi , Ghazal Kiani , Jay Shravah , Rajvir Shahi and Brian Conway

Tyler Raycraft1,2, Syune Hakobyan1, Sahand Vafadary1, Arshia Alimohammadi1, Ghazal Kiani1, Jay Shravah1, Rajvir Shahi1 and Brian Conway1*

1Vancouver ID Research and Care Centre Society, Vancouver, Canada

2University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada

- *Corresponding Author:

- Brian Conway

Vancouver Infectious Diseases Centre, 201- 1200 Burrard St., Vancouver, BC, Canada

Tel: 6046426429

Email: Brian.Conway@vidc.ca

Received date: September 28, 2015; Accepted date: December 08, 2015; Published date: December 16, 2015

Citation: Raycraft T, Hakobyan S, Vafadary S, et al. Retrospective Analysis of Recurrent HCV Viremia in High-risk HIV Co-infected People Who Inject Drugs (PWID). J Hep. 2016, 2:2

Copyright: © 2016 Raycraft T et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Background: People who inject drugs (PWID) are overrepresented in the HCV-infected community. Past Canadian guidelines do not advocate HCV treatment of HIV co-infected PWID, fearing reduced ĞĸcĂcy and recurrent viremia ĂŌĞr successful treatment, due to ongoing risk behaviours. These factors may be more prominent among those co-infected with HIV.

Methods: A Retrospective chart review analysis was performed to identify HIV/HCV co-infected individuals who actively injected drugs within 6 months preceding or during HCV treatment. Information regarding ƉĂƟĞnƚ cŚĂrĂcƚĞrÃ…ÂÂÆÂÂƟcÆÂÂÕ risk behaviours, HCV treatment, and virologic follow-up post-treatment was collected.

Results: We identified 45 HIV/HCV co-infected PWID (mean age 51.9 years, 6.7% female, 57.8% on opiatesubstitution therapy, 66.7% genotype 1, 82.2% treatment naïve, 73.3% on interferon-based therapies, and 1.52 person years of follow-up/subject). Following successful HCV therapy, 3 cases of HCV recurrent viremia were identified

Conclusion: HCV Ã…ÂÂnĨĞcƟŽn can be successfully treated in high-risk HIV co-infected individuals. In our unique ÆÂÂĞƫnÃ…ÂÂÕ few cases of recurrent viremia were identified in mediumterm follow-up.

Keywords

HCV-infected community; Retrospective analysis; Recurrent viremia; Interferon-based therapies

Introduction

People who inject drugs (PWID) are overrepresented in the HCV-infected community, while up to 22.8% of this population is also co-infected with HIV [1]. Although a number of strategies have been developed to engage these individuals in care, past Canadian guidelines did not advocate HCV treatment of HIV co-infected PWID due to reduced efficacy in the setting of HIV co-infection and the higher risk of recurrent viremia after successful treatment. In this context, an abstinence period was mandated to ensure that risk behaviours regarding drug injection were properly mitigated [2]. Current guidelines do not call for an abstinence period, but rather suggest treatment be undertaken within a multidisciplinary setting [3]. Many caregivers still withhold HCV treatment of HIV/HCV co-infected PWID [4,5], despite the fact that management of HIV infection may actually be more effective once the HCV infection is cleared [6].

Some data suggest that high rates of recurrent viremia (13% and 21% in HCV mono- and HIV co-infected PWID, respectively) have been reported when therapy is delivered using traditional models of care and engagement [7,8], without the multidisciplinary aspects of care that are recommended in this population.

Interferon-based regimens have led to cure rates of 50-70% [9,10] or even lower among HIV co-infected individuals. Newer, all-oral, direct acting antiviral therapies (DAA) have been producing SVR rates exceeding 90%, with little or no toxicity and regimens administered over 8-12 weeks. Interestingly, the SVR rates are not affected by the presence of HIV co-infection [11].

Our program has extensive experience in the development of systems of care for marginalized HIV/HCV co-infected individuals, using a novel model of multidisciplinary outreach and engagement. We report on the success rate of HCV therapy in this setting, along with the rate of recurrent viremia when long-term engagement in care after the end of HCV therapy is provided.

Methods

Patient selection

A retrospective, comprehensive chart review was performed, including records of all patients receiving care on a regular basis at the Vancouver Infectious Diseases Centre (VIDC). This analysis includes consenting adults (18 years of age or older) chronically infected with HIV and HCV, receiving HCV therapy, and with a record of recreational drug use in the previous 6 months (including during the time of HCV therapy).

Model of care

All VIDC patients have access to comprehensive multidisciplinary care with nurses, primary care and specialty physicians, study coordinators, and support staff. The goal of this program is to address psychiatric, addiction-related, and social needs in an integrated manner along with traditional medical care.

We also utilize this model to further engage patients and provide them with peer-friendly education, cutting-edge antiviral therapeutic options, and general support prior to and during treatment.

Another tool of engagement of patients within this model is the organization of a weekly support group for HCV infected patients, facilitated by a member of the clinic staff. Patients participating in the group share their experiences, expectations, and achievements with other members of the group in a friendly and non-judgmental atmosphere. This allows for an open discussion about the factors contributing to the acquisition of disease and will allow the healthcare professionals to have a forum to educate patients about their illness, and ways of dealing with it in a productive manner. Topics discussed include all aspects of patient care including social issues, addiction management, and pathophysiology of the disease.

Data collection and end point

Data collected for patients that met the inclusion criteria included demographic variables, infection status, treatment status, ongoing recreational drug use, and follow-up duration. The primary endpoint was a sustained virologic response (SVR), defined as undetectable HCV viral load for at least 12 weeks post-treatment, as well as documentation of recurrent HCV viremia within the context of long-term follow-up. All procedures were conducted with the approval of the relevant research ethics boards.

Results

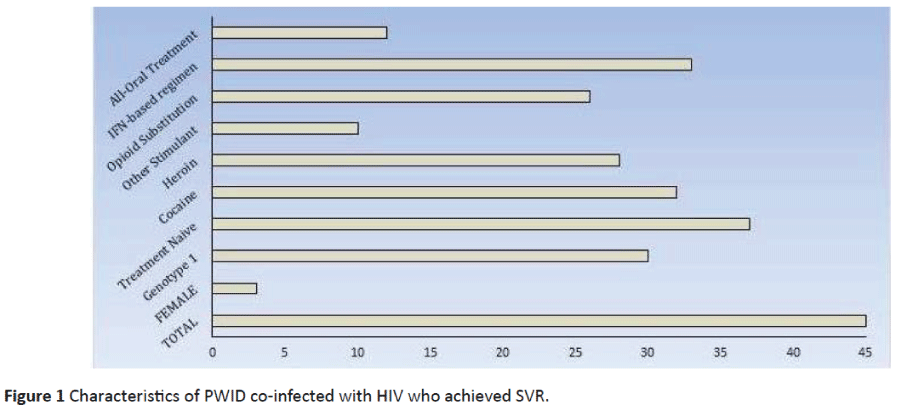

Within our cohort, we identified 192 individuals co-infected with HIV and HCV, with 145 of them being PWID. Through our program, we treated 45 individuals who were actively injecting drugs (as defined above) and who achieved SVR. Within this cohort, the mean age was 51.9 (range 38-67) years, 3 (6.7%) were female, 30 (66.7%) were genotype 1, and 37 (82.2%) were previously treatment naïve. The mean number of HCV treatments, including the regimen achieving SVR, was 1.14 (range 1-2). The dominant forms of drug use included cocaine (71.1%), heroin (62.2%), and other stimulant use (22.2%). In addition, 26 (57.8%) patients were receiving opiate substitution therapy. In total, 33 (73.3%) patients received interferon-based regimens and 12 (26.7%) received all-oral regimens. In a mean of 1.52 person-years of follow-up/subject, 3 cases of HCV recurrent viremia were noted (Figure 1).

The characteristics of these 3 subjects were as follows

Subject #1: This is a 50 year-old male on methadone substitution therapy, actively using recreational opioids and cocaine. He has multiple concurrent diseases (including bipolar disorder) and is functionally homeless. Current antiretroviral medications are abacavir, lamivudine and maraviroc with full virologic suppression.

He initially received ribavirin and pegylated interferon for his HCV genotype 1a infection and SVR was documented. HCV plasma viral load done 14 weeks after SVR was achieved was positive, showing HCV Genotype 2b/3a with an HCV RNA of 2.9 million copies/mL. His most recent fibroscan score was 9.3 kPa (Stage 2 fibrosis).

Subject #2: This is a 61 year-old male on opiate substitution therapy, actively using recreational benzodiazepines and opioids (including heroin). He has multiple concurrent diseases (including depression) and is functionally homeless. Current antiretroviral medication is single tablet Stribild (a combination of tenofovir, emtricitabine, elvitegravir, and cobicistat) with full virologic suppression. He initially received ribavirin and pegylated interferon for his HCV genotype 1a infection for 24 weeks and SVR was documented. HCV plasma viral load done 15 weeks after SVR was achieved was positive, showing HCV genotype 1a, with an HCV RNA of 1.2 million copies/mL. His most recent Fibroscan score was 3.8 KPa (stage 0 fibrosis).

Subject # 3: This is a 47 year-old male on opiate substitution therapy, actively using recreational cocaine. He has multiple concurrent diseases (including schizophrenia) and has stable housing. Current antiretroviral medications are Kaletra (lopinavir and ritonavir) and maraviroc with full virologic suppression. He initially received ribavirin and pegylated interferon for his HCV genotype 1a infection for 24 weeks and SVR was documented. HCV plasma viral load done 8 weeks after SVR was positive with HCV genotype 1a, with an HCV RNA of 3.2 million copies/mL. His most recent Fibroscan was 7.3 kPa (stage 0-1 fibrosis) (Table 1).

| Category | Subject # 1 | Subject # 2 | Subject # 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 50 | 61 | 47 |

| Sex | Male | Male | Male |

| Opiate Substitution Therapy | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Recreational Drug Use | Opioids, Cocaine | Opioids | Cocaine |

| Anti-Retroviral Therapy | Abavacir, lamivudine, maraviroc | Stribild | Kaletra, maraviroc |

| Most recent HIV RNA | <40 copies/mL | <40 copies/mL | <40 copies/mL |

| Most recent HCV Genotype | 2b/3a | 1a | 1a |

| Most Recent HCV RNA | 2.9 million copies/mL | 1.2 million copies/mL | 3.2 million copies/mL |

| Most Recent Fibroscan® Score | 9.3 KPa | 3.8 KPa | 7.3 KPa |

| Most Recent HCV Treatment Regimen | Ribavirin + IFN | Ribavirin + IFN | Ribavirin + IFN |

| Psychiatric disorder | Bipolar Disorder | Depression | Schizophrenia |

| Homeless? | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Table 1: Subjectwise Reports.

Discussion

It is well demonstrated that the social determinants of health, such as housing, availability of social and welfare support, and stigma associated with HCV infection translate directly into reduced treatment uptake and adherence by the patients. This directly results in the traditionally observed lower rates of SVR among HCV-infected PWID [12]. Our research demonstrates that with proper engagement of HIV/HCV co-infected PWID into care and facilitation of access to social services (disability applications, shared housing, and nutritional support), along with the provision of in-house addiction and psychological counseling services, proper engagement in care can occur and significant numbers of patients can be successfully treated for their HCV infection.

Multiple barriers at multiple levels have traditionally contributed to the lower levels of screening, engagement, and treatment of HCV-infected PWID. It is suggested that the lack of systematic testing strategies to address this challenging population, lack of education about HCV disease, concerns regarding treatment adherence, and psychological stability of this patient population all contribute to the reduced uptake of HCV treatment among vulnerable populations, especially PWID [13].

Although recent guidelines for the management of HCV have recommended inclusion of people actively injecting drugs in treatment programs, health care professionals remain hesitant due to concerns about recurrent viremia after successful therapy [11]. However, within a multidisciplinary model such as ours, this risk appears to be significantly mitigated.

Within the cohort of 45 HIV-HCV co-infected PWID who had achieved HCV SVR, most individuals were mixed drug (opioid and stimulant) users. The study population was predominantly male and the vast majority of patients (as expected) were treatment naïve. With an average of 1.52 person-years of follow-up/subject, there were only 3 cases of recurrent viremia, a significantly lower rate than those reported in previous studies of similar populations [1]. We believe this can be attributed to the model of care provided at VIDC and the structured post-SVR follow-up schedule applied to all patients, which helps reduce on-going risk behaviours that could transmit HCV infection.

All three of our patients with recurrent viremia had concurrent psychological disorders, and two of three were homeless. It may be that novel approaches to acting on these conditions, in addition to the care model we are already providing, will serve to reduce rates of recurrent viremia even lower.

In conclusion, our significant cohort of HCV/HIV co-infected PWID successfully treated for their HCV infection demonstrates the importance of a multidisciplinary approach to management to achieve successful engagement in care and treatment in HCV-infected PWID. This model, we believe, will also help reduce the rate of recurrent viremia post-treatment that has been a great concern in addressing the HCV pandemic in vulnerable inner city populations. With the advent of all-oral regimens, even more PWID can be recruited into care and more effectively treated. The provision of medical care in a model such as ours will maximize the benefits of these highly effective (and also highly expensive) interventions.

Acknowledgment

We would like to acknowledge the wonderful work of the staff at the Vancouver Infectious Diseases Centre, without whom the multidisciplinary patient care model could not have been achieved. We also recognise the generosity of the patients who have selflessly volunteered to be part of our research programs.

Funding

We recognize the support of the National Clinical Research Training Program on HCV (BC, program mentor) and for salary support to AA & TR.

References

- Public Health Agency of Canada (2011) Hepatitis C in Canada: 2005-2010 Surveillance Report. Centre for Communicable Diseases and Infection Control, Infectious Disease Prevention and Control Branch, Public Health Agency of Canada.

- Sherman M, Shafran S, Burak K (2007) Management of chronic hepatitis C: consensus guidelines. Can J Gastroenterol21: 25C-34C.

- Myers RP, Shah H, Burak KW, Cooper C, Feld JJ (2015) An update on the management of chronic hepatitis C: 2015 Consensus guidelines from the Canadian Association for the Study of the Liver. Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 29: 19-34.

- Ingiliz P, Krznaric I, Stellbrink HJ, Knecht G, Lutz T, et al. (2014) Multiple hepatitis C virus (HCV) reinfections in HIV positive men who have sex with men: no influence of HCV genotype switch or interleukin 28B genotype on spontaneous clearance. HIV medicine 15: 355-361.

- Wiessing L, Ferri M, Grady B, Kantazanou M, Sperle I, et al. (2014) Hepatitis C Virus Infection Epidemiology among People Who Inject Drugs in Europe: A Systematic Review of Data for Scaling Up Treatment and Prevention. PLoS ONE9: e103345.

- Tien PC (2005) Management and Treatment of Hepatitis C Virus Infection in HIV-Infected Adults: Recommendations from the Veterans Affairs Hepatitis C Resource Center Program. The American journal of gastroenterology 100: 2338-2354.

- Grady BP, Schinkel J, Thomas X, Dalgard O (2013) Hepatitis C Virus Reinfection Following Treatment Among People Who Use Drugs. Clin Infect Dis 57: 105-110.

- Hill A, Simmons B, Saleem J, Cooke G (2015) Risk of late relapse or re-infection with hepatitis C after sustained virological response: meta-analysis of 66 studies in 11,071 patients. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Seattle.

- Backmund M, Meyer K, Von Zielonka M, Eichenlaub D (2001) Treatment of hepatitis C infection in injection drug users. Hepatology34: 188-193.

- Hellard M, Sacks-Davis R, Gold J (2009) Hepatitis C treatment for injection drug users: a review of the available evidence. Clin Infect Dis 49: 561-573.

- Hsieh YL, Tossonian H, Sharma S, Conway B (2015) Benefit of DAA-based HCV therapy in mono-infected vs. HIV co-infected inner city populations. CAHR.

- Barriers and facilitators to hepatitis C treatment for people who inject drugs (2016) A qualitative study.

- Grebely J, Oser M, Taylor LE, Dore GJ (2013) Breaking down the barriers to hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment among individuals with HCV/HIV coinfection: action required at the system, provider, and patient levels. J Infect Dis 2071:S19-25.

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences